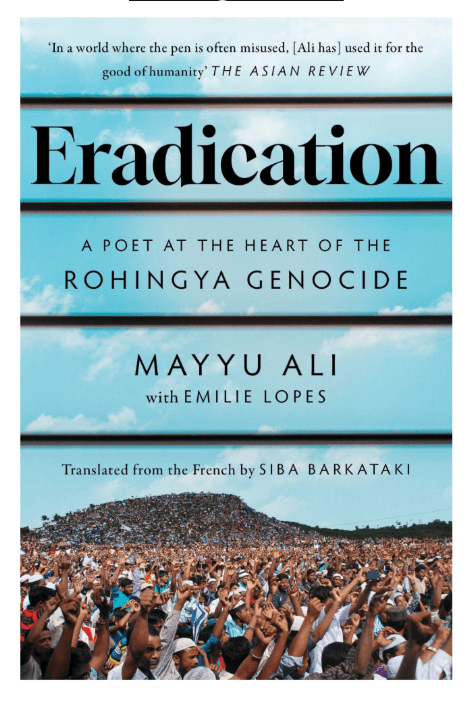

Some stories scream; others whisper — and yet their echoes can shake the world. Eradication: A Poet at the Heart of the Rohingya Genocide by Mayyu Ali, co-written with Emilie Lopes and translated by Siba Barkataki, belongs to the latter kind. It is not a loud book. It doesn’t rage or accuse. It simply bleeds truth — line by line, memory by memory — until silence itself feels complicit.

For decades, the world has known the Rohingya tragedy in numbers: 740,000 refugees, 1982 citizenship law, dozens of massacres, countless lost homes. But statistics don’t weep. They don’t carry the scent of burning fields or the ache of a name erased from official records. Mayyu Ali gives those numbers a heartbeat. His memoir is not written to explain the genocide — it is written to feel it, to make readers inhabit the skin of a people declared invisible.

Ali’s journey from a boy in Myanmar’s Arakan region to an exiled poet in Canada reads like a history of endurance carved into human flesh. Once a child who dreamt of teaching, he grew up in a nation that stripped him of identity, banned him from education, and told him his very existence was illegal. What the state denied him in papers, he reclaimed in poetry.

“Every night, I am killed. Every morning, I wake up again.”

That haunting refrain, which opens the book, is both metaphor and manifesto. It captures the daily death and rebirth of a persecuted people — and of the poet himself.

A Voice from the Ashes

Every so often, a book arrives that doesn’t just tell a story — it forces the reader to look, to feel, and to reckon. Eradication: A Poet at the Heart of the Rohingya Genocide by Mayyu Ali (with journalist Emilie Lopes and translated by Siba Barkataki) is one such book. It’s not merely a memoir; it’s an open wound stitched with words, an anthem of survival in the face of annihilation.

Ali, a poet and activist, belongs to the Rohingya — the world’s largest stateless people, denied citizenship in their own country of Myanmar since 1982. His life has been defined by displacement, yet also by defiance. Through the rhythm of his poetry and the urgency of his prose, Eradication transforms pain into protest and memory into a form of resistance.

This book is a mirror held up to a world that too easily scrolls past suffering.

The Making of a Witness

Ali’s childhood in Myanmar’s Arakan (Rakhine) region was once idyllic — a shared life with Buddhist and Hindu neighbours, simple joys, the smell of rain on paddy fields. But that peace was gradually corroded by propaganda. State-led hate campaigns turned community against community, slowly teaching citizens to mistrust, then to hate, the people they had grown up beside.

“Our own land had become the burial ground of our culture.”

That one sentence captures the slow-motion violence that precedes genocide: the erasure of dignity before the destruction of lives.

As the Rohingya were stripped of rights — banned from higher education, denied property, and labeled “foreigners” — Ali found refuge in language. Writing was his rebellion. His first poem, published under a pseudonym, was not just an act of creativity but of existence. “They could erase my name,” he writes, “but writing would allow me to leave an indelible mark.”

The Fire and the Flight

When the Myanmar military launched its brutal “clearance operations” in 2017, over 740,000 Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh. Villages were burned, families torn apart, and bodies buried in shallow graves.

Ali and his family were among those forced to flee. Inside the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, the world’s largest, he became both chronicler and counselor — recording atrocities for the UN and foreign journalists, while helping his community survive with dignity.

He describes mass graves, girls violated, children burnt alive. But beneath these horrors, the reader finds moments of courage — a mother hiding her son in a rice sack, a boy smuggling books instead of bread.

“Writing wasn’t a vocation; it was the only solution for my disturbed psyche — a shield that protected me.”

Even as his activism made him a target of the militant Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, Ali continued to teach and write. His resilience — fragile but luminous — becomes the book’s heartbeat.

The Pen as a Refuge

While Eradication is drenched in grief, it is equally a testament to the transformative power of art. Ali founded The Art Garden Rohingya, a creative collective in the camps, offering poetry, painting, and storytelling as tools for mental healing. He introduced Burmese school curricula, initiated writing therapy for trauma survivors, and began documenting Rohingya oral traditions.

Ali’s resistance is not loud. It is deliberate, meticulous, and deeply human — a rebellion through preservation.

His partnership with French journalist Emilie Lopes and translator Siba Barkataki elevates the book from memoir to movement. Lopes brings narrative clarity, grounding Ali’s memories in global context, while Barkataki’s translation captures the poetic cadence of Ali’s voice without losing its rawness.

Echoes of Genocide: Lessons the World Forgot

Reading Eradication feels like déjà vu — history repeating itself in a different language. From Nazi Germany to Rwanda to Gaza, the patterns of persecution remain painfully familiar. A regime manufactures hate; the majority complies or stays silent; the minority disappears.

Ali dismantles the myth that genocide belongs to the past. “It is not over,” his narrative insists. “It just changes its mask.”

The book also reveals a darker irony: the same Myanmar that birthed global peace icon Aung San Suu Kyi also became the stage for one of this century’s worst ethnic cleansings — a paradox that Ali confronts without bitterness, but with heartbreak.

Between Exile and Eternity

In 2021, after years in hiding, Ali was granted asylum in Canada. There, free from fear for the first time, he continued his mission — advocating for Rohingya rights, preserving their endangered language, and earning a master’s degree in Global Governance.

But freedom, he admits, feels incomplete. His parents and siblings remain in refugee camps. His homeland remains closed. “To be free,” he writes, “is not enough when your people are not.”

“They burned our homes. But they will never burn our stories.”

That line — simple, resolute — encapsulates the soul of Eradication. It’s not a story of escape, but of endurance.

Why This Book Matters Now

Eradication arrives at a time when the world is drowning in images of war, displacement, and despair — Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan. The Rohingya crisis has largely faded from headlines, yet Ali’s memoir reignites its urgency.

It reminds us that forgetting is the final victory of oppression. The book is a call to remember — not out of pity, but out of duty.

Ali’s courage also redefines what activism looks like. In a world obsessed with loud protests, his resistance is quiet and persistent — a poem written under curfew, a classroom in a tent, a language kept alive through a lullaby.

The Craft of Collaboration

Much of the book’s power lies in its three-way authorship. Emilie Lopes shapes Ali’s memories with journalistic clarity, guiding the reader through layers of personal and political history. Translator Siba Barkataki, a scholar of Francophone literature, renders the text into English with rare sensitivity — maintaining its lyricism while ensuring accessibility.

Together, they transform Ali’s experience into something larger than memoir — a document of collective memory, meant to outlast both violence and time.

A Testament, Not a Tragedy

Ultimately, Eradication is not about victimhood; it is about reclamation. It insists that identity, language, and love can survive even the machinery of genocide.

For the reader, the experience is humbling — a reminder that while we debate policy and politics, real people are building schools in tents, composing poems in exile, and documenting history with borrowed pens.

Ali’s story may be rooted in Myanmar, but its echo stretches far beyond. It speaks to anyone who has been silenced, displaced, or forgotten — and to everyone who has ever chosen to look away.

Pull Quotes for Publication:

“Genocide begins not with bullets, but with bureaucracy — a revoked birth certificate, a slur, a silence.”

“They burned our homes. But they will never burn our stories.”

“Writing became my way to exist in a world that denied my existence.”

Final Reflection: The Unkillable Word

Closing Eradication feels like waking from a nightmare — but also from complacency. Ali’s endurance, his stubborn faith in the written word, reaffirms something essential about the human spirit.

This is not a comfortable read — but it is a necessary one. It demands attention, empathy, and, above all, remembrance.

Rating: ★★★★★ (5/5)

A devastating, lyrical, and vital memoir that refuses to let history bury the living. Mayyu Ali’s pen does what no weapon can — it keeps his people alive.

Leave a comment